When it comes to equity, community colleges are essential for taking the state of Illinois from where we are today to the bright future we imagine for ourselves tomorrow.

Acknowledgments

This report was completed with support from the Steans Family Foundation and PCC’s Investors Council. The report was authored by Dr. Frank Fernandez, Assistant Professor of Higher Education Administration & Policy, Institute of Higher Education at the University of Florida, Dr. Xiaodan Hu, Associate Professor of Higher Education and Student Affairs at Northern Illinois University, with support from Partnership for College Completion’s Mike Abrahamson, Caitlin Power, and Giselle Palacios. It was made possible with editing from Abigail Higgins. We would also like to thank our many partners and colleagues who generously reviewed and advised this report. As always, our work would not be possible without the deep commitment and ongoing support of so many individuals, including the PCC Board of Directors, PCC Investors Council, college and university partners, legislative champions, colleagues within state agencies and government, and advocates.

Letter from the Board Chair and the Executive Director

When it comes to equity, community colleges are essential for taking the state of Illinois from where we are today to the bright future we imagine for ourselves tomorrow. This sector serves more students from low-income backgrounds and students of color than any other, offering a pathway to prosperity for those who choose community college at different points in their lives for many reasons, given these institutions’ diverse missions. They also serve students who may not be able to access public and private four-year institutions. Our future economy will require a workforce that is more educated than ever before, making community colleges essential from a statewide economic development perspective. Despite this, enrollment is at alarmingly low levels: 316,000 fewer students – including 69,000 fewer Black students – were enrolled in community colleges in 2022 than in 2012.1

Students, local communities, and the state are meant to share the responsibility for funding these lower-cost, high-reward centers of learning. Unfortunately, the state has abdicated its role over the last two decades forcing students to pick up the bill and fueling today’s enrollment decline. This is in turn feeding a budding economic crisis, as employers say they can’t find qualified Illinoisans for the jobs they’re offering, while thousands of potential college graduates forgo higher education because it is too expensive. When they can afford it, students often must take fewer courses at a time, take longer to graduate, or end up not finishing at all.

This report lifts up an urgent call to restore public funding to community colleges. Over the years, we’ve heard that, given current revenue, the state can’t afford to give these institutions and their students the funding they need to succeed. While revenue concerns are immediate and colleges’ return on investment may seem more remote, the two are directly connected. If we can’t turn around our enrollment and completion trends, our economy will continue to stratify, primarily benefiting those born with the resources to pay their own way through higher education and creating a gulf of opportunity between those who cannot.

However, there’s an alternate path. If we provide our 48 community colleges throughout Illinois with better and more targeted funding, these institutions will enroll and graduate more students, allowing them to fill the well-paying jobs of tomorrow and have families who enjoy prosperity and social mobility. Moreover, each graduate will pay thousands of dollars more in state taxes every year than they would have without a degree. The economy won’t just be robust, it will be more inclusive, with graduates of every background and geography across the state filling jobs that can bring generational wealth and stability. That is good for families and that is good for the state.

This report explores how much state funding might be needed to equitably serve community college students, as well as the potential impacts of more funding, and how to most effectively and equitably direct it. We are advocating for higher education to be treated as a public good in this state, affordable and accessible for all who seek it. Increasing our investment in community college is essential for our long-term economic health, one that will more than pay for itself in the long run.

Lisa Castillo Richmond, Ph.D.

PCC Executive Director

Dr. Doug E. Wood

PCC Board Chair

Executive Summary

Advancing Adequacy-Based Funding for Community Colleges in Illinois dives deep into Illinois’ disinvestment in its community colleges over the past three decades, uncovering damaging effects on our institutions, future economy, and students. As Illinois has decreased its higher education spending from 12.5% of its discretionary spending in 1991 to just 2.7% in 2022, community colleges have been least able to bring in other revenue.2 Instead, they’ve had to raise tuition, threatening their ability to serve students and causing enrollment to spiral over the last ten years. However, this report charts an alternate path of investment in higher education, using state data and extensive research to show the transformative potential of that funding. Below is a summary of the findings of this report.

Findings

1. Community colleges offer an affordable pathway to greater earnings.

- Illinois residents with an associate degree earned about $12,000 more each year than those with a high school diploma.

2. Community college enrollment declines have been worse in Illinois than in other states.

- Enrollment in Illinois community colleges declined by 44% from 2012-2022.

- Black student enrollment declined by 59% from 2012-2022.

3. There has been substantial state disinvestment along with subsequent tuition increases.

- State appropriations to Illinois community colleges declined by 23% from 2004-2023.

- Tuition and fees increased at community colleges by 65% from 2004-2020.

- Students who live alone average $11,000 in uncovered costs after state and federal aid.

4. State legislators fund community colleges at 23% of what the Illinois Community College Board (ICCB) estimates they need.

- The annual deficit has increased from $98M in 2010 to $637M in 2021.

- Community colleges lose less money when they place students in developmental. education and lose more money when they place students in high-cost programs, creating a perverse incentive.

Recommendations

1. Fully fund grants and reduce tuition reliance.

- State legislators should fully fund ICCB’s budget recommendations in base operating costs and equalization grants.

- Appropriate funding to bring tuition and fees in line with the national average.

- Provide cost of attendance relief funds to low-income students to offset costs. Uncovered by the Monetary Award Program (MAP) and Pell.

2. Fund implementation of the Developmental Education Reform Act (DERA).

- State mandates like DERA require upfront resources to implement and scale.

- The state should incentivize and fund co-requisite models of support.

3. Equitably fund student success.

- Rather than aiming for neutrality, the state should focus on equitably closing funding gaps.

- The state should increase funding for curricular and co-curricular programming and supports.

4. Hold institutions accountable in ways that encourage innovation.

- Move toward accountability that holistically serves students and colleges.

- Funding should encourage innovation, effective practices, and transformational change.

Section I

Introduction

There is a demographic educational crisis in Illinois. Among 48 institutions in 39 districts, Illinois community colleges serve about 600,000 students each year.3 However, enrollment declined between 2019 and 2021, surpassing declines in surrounding states (Figure 1).4 This pattern is driven, in part, by Black student enrollment declines. In 2012, more than 117,000 Black students enrolled at Illinois community colleges, but by 2022 that number dropped to under 48,000.5 While Black student enrollment has declined across multiple sectors of higher education, the worst has been in community colleges.6 All of this contributes to a unique and concerning trend: unlike Asian, Latinx, and White Illinois residents, educational attainment is decreasing for younger Black residents (Figure 2).

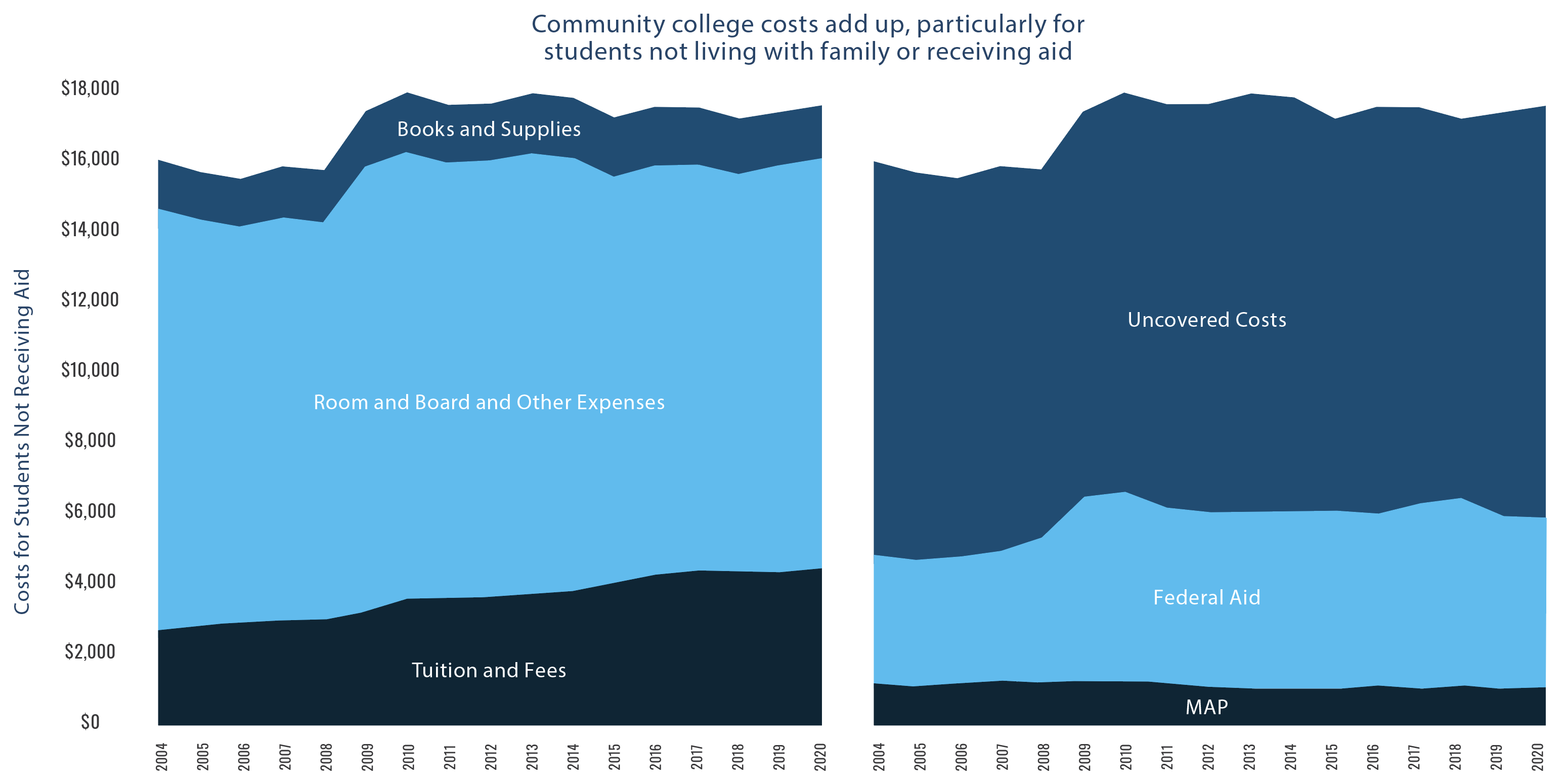

The troubling enrollment decline parallels substantial disinvestment (23%) in state and local appropriations to community colleges between 2001 and 2011. As appropriations decreased, public community colleges increased their cost of tuition and fees by 47.3% during the same period. This was part of a national trend.7 By 2023-24, the estimated national average cost of tuition, fees, and room and board led to an annual cost of $13,960. With additional expenses such as books and supplies, the national average published cost of attending community college was $19,860 per year. 8

Figure 1: Percentage Changes in Total Undergraduate Enrollment in Public Two-Year Institutions (2019-2021)

Figure 2: Percentage Change in Postsecondary Attainment Between Younger (25-35) and Older (25-64) Cohorts of Illinois Residents by Race (2009-2019)

Note: Authors’ calculation based on data from the Lumina Foundation.9

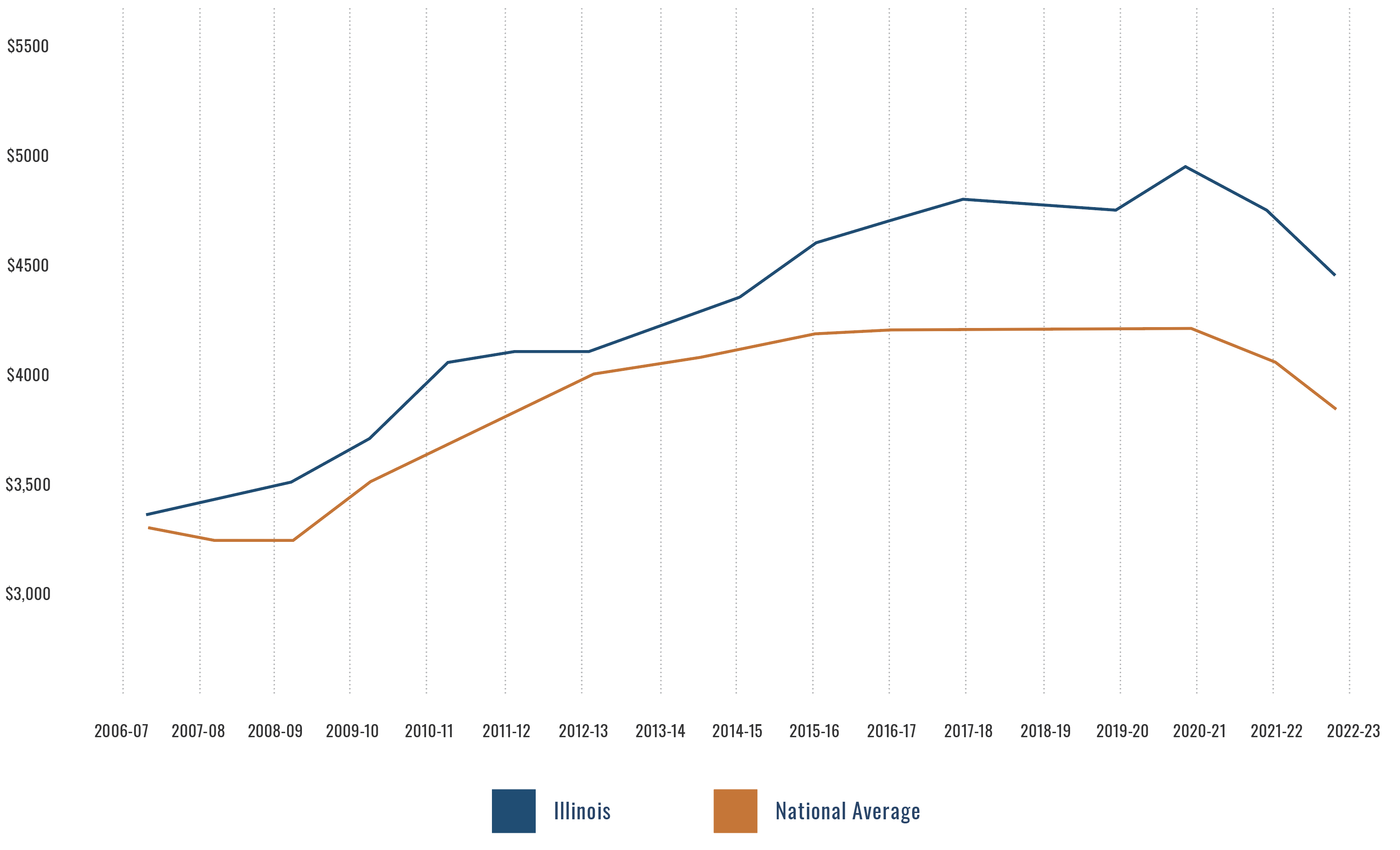

Although the cost of attending community college has increased around the country, in Illinois tuition and fee increases for attending two-year colleges outpaced the national average (Figure 3). Due to the state’s 2016-2017 budget impasse and subsequent suspension of the largest need-based financial aid program, community colleges experienced major tuition increases, enrollment declines, layoffs, and loss in economic output.10 Illinois never closed the community college affordability gap in the years that followed.

Illinois community colleges can offer some of the best opportunities for students to attain affordable and accessible degrees that help them get better, higher paying jobs. Illinois residents with an associate degree earned around $12,000 more per year than those who only graduated from high school.11 For rural students in particular, community college is the best chance to enroll in higher education. Although graduates of rural high schools are less likely to go to college than those of urban high schools, approximately two-thirds of rural students who do enroll in public higher education enroll in community college (compared to less than 50% for urban students).12

In this report, we examine how Illinois funds its community colleges and advocate for alternative funding strategies that may make community colleges more affordable, reverse colleges’ reliance on increasing student tuition, and support community colleges with adequate resources to achieve equitable outcomes such as degree attainment. In the next section, we briefly summarize prior research on how states can adequately fund public community colleges. After that, we examine Illinois-specific legislation and funding formulas for these institutions. Then, we consider potential incentives and unintended consequences of current funding policies. Finally, we offer recommendations to consider how adequate funding may help serve broader goals of improving community college equity, access, and completion.

Figure 3: Average Public Two-Year In-District Tuition and Fees

Note: Authors’ calculation based on data from the College Board.13 Data presented in 2023 dollars.

Section II

Background

Scholars have looked to litigation and the formulas used for adequately funding K-12 public schools to consider how to equitably fund community colleges.14 A Century Foundation report concluded that “preliminary analyses applying PreK-12 equity frameworks suggest that state community college systems fail to meet even the most basic equity standards.”15 Community colleges are forced to reduce expenditures below what it takes to educate their disproportionately low-income, racial minority, and rural students. Despite serving many students who experienced disinvestment across their PreK-12 journey, community colleges have less to spend per student than other types of public and private colleges.16

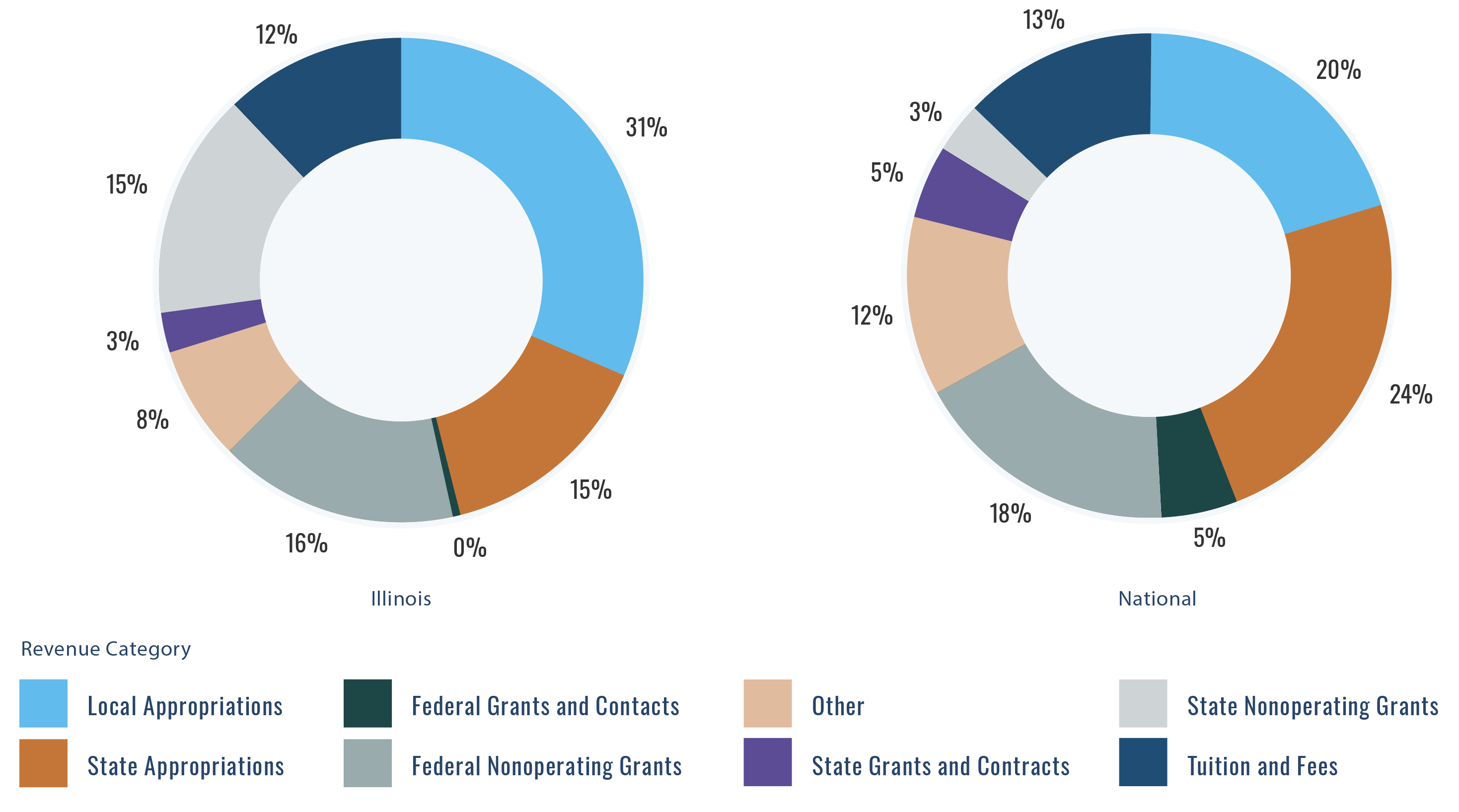

Prior literature on community college student success has repeatedly indicated that community colleges should be sufficiently funded to expand student access, improve student experiences, and improve measurable outcomes such as academic performance, retention, upward transfer, completion, and job placement.17 Although community colleges draw revenues from a variety of sources (as presented in Figure 4), not all forms of revenues have similar effects on student success. For instance, community colleges have raised tuition and fees as a response to reductions in state funding, but prior research shows that public financial support is better for college attendance and completion than revenue from tuition and fees.19 Therefore, it is essential to provide adequate and equitable public funding for community colleges.

Figure 4: Illinois and National Snapshot of Sources of Institutional Revenues for Public Community Colleges, 2021-2022

Note: Authors’ calculation based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System.18

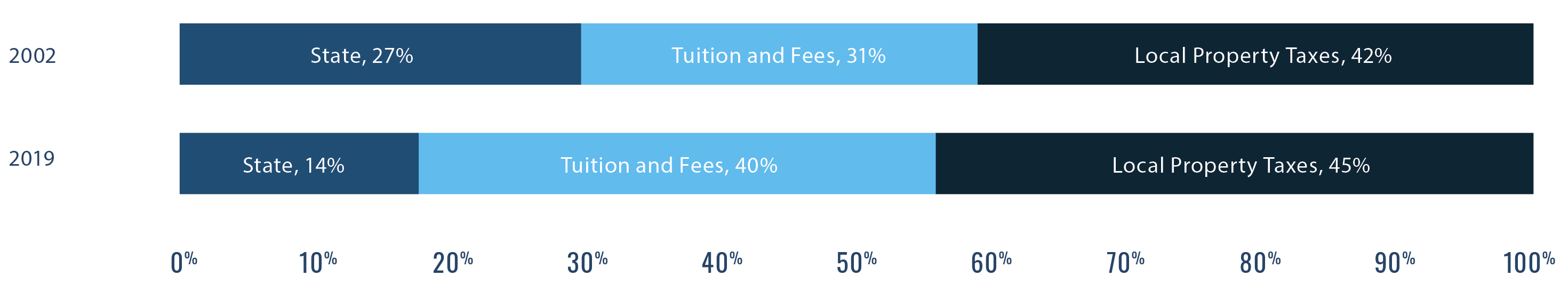

States fund community colleges using different models to achieve various outcomes.20 Since its inception, the funding philosophy for the Illinois community college system has expected the student to be a substantial contributor to institutional funding by allowing “community colleges to enact a tuition and fee charge up to one-third of the per-capita cost of education.”21 While the principle remains, the balance has shifted: In 2002, more than one-quarter of community college expenses in Illinois came from state appropriations but by 2019 that share had decreased to 14%. Most of that gap has been made up by increases in tuition and fees incurred by students and their families, with a smaller share coming from collecting more in local property taxes (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Changes in Sources of Illinois Community College Revenues

Note: Authors’ representation of data from the Illinois Board of Higher Education.22

To its credit, Illinois has relative parity in how it funds community colleges within the state. In other words, Illinois has achieved “neutrality” in reducing funding disparities between counties with low or high-property tax bases.23 The challenge, however, is that giving two different community colleges similar levels of funding may still not be adequate or equitable when those two colleges serve different populations with different needs — not to mention that differences in cost of living impact what is considered a competitive staff and faculty salary. Adequate and equitable funding should go beyond neutrality and instead respond “to both differences in community wealth and student need.”24 In the sections that follow, we consider how Illinois can move beyond neutralizing differences in funding across colleges to consider how institutional and student needs vary across the state.

Section III

Current Funding Formulas for Illinois Community Colleges

The use of public funds to support community colleges has been considered an investment in the collective good of the community, but state support has been gradually declining for Illinois community colleges. According to data from the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) in Figure 6, the national average percentage of state expenditures on higher education overall (excluding federal revenue as pass-throughs) remained stable at around 15% between FY1991 and FY2022. However, for Illinois, the longitudinal trend indicated a substantial decline in state support for all its colleges and universities, going from 12.5% in 1991 to just 2.7% in 2022. The 2016-17 budget impasse is one example of how community college revenue from the state government is susceptible to both economic conditions and political factors.25 For Illinois, the percentage of state expenditures devoted to overall higher education bottomed out at 1.7% in 2016.

It is common for the community college sector to receive a smaller share of state funds compared to the four-year sector.26 In Illinois, this difference is also because community colleges receive local revenues from property taxes while four-year universities do not. This arrangement was a result of Illinois’ Junior College Act of 1965 which set the expectation that local control and interest remain strong in community college funding and governance. In addition to student tuition and fee revenue, two-thirds of the cost of running each college was meant to come equally from state funding and local property tax revenue.

Figure 6: Percentage of State Expenditure on Higher Education Overall Between FY1991 and FY2022

Overreliance on Local Property Taxes

According to a report from the Center for American Progress (CAP), 24 states provide local funding to public community colleges generated primarily through local property taxes.27 Like Illinois’ one-third funding philosophy, public community colleges in Wisconsin and Michigan receive about a third of their revenue from local appropriations. Conversely, states like Indiana and Kentucky do not collect local funding to support community colleges.28 Geographic locations and wealth disparities in the local community can lead to revenue disparities among community colleges. For example, community colleges in urban settings often face more challenges securing revenue through government funding compared with those located in towns and rural areas.29 Community colleges with a greater reliance on local funds tend to have lower tuition, on average, than those that rely more on state funds.30

In Illinois, local property tax revenue has made up substantially larger percentages of community college revenue as the share of state appropriations has declined. Similar to our calculations (Figure 4 above), national organizations estimate that between 45% and 50% of revenue to Illinois’ public community colleges comes through local appropriations.31 Nationally, public community colleges receive an average of 32% of their revenue from local sources.

For some states, CAP recommended increasing local property tax or the share of local property tax revenue to improve funding across a state’s community colleges. However, Illinois is already highly reliant on funding community colleges through local property tax revenue, which could lead to inequity.32 Therefore, CAP concluded that “local communities . . . are already bearing too much of the burden” and what is needed is “for the state to reinvest in community colleges to help close the resource gap and allow these institutions to see their students to greater success.”33

State Funding Level and Change Over Time

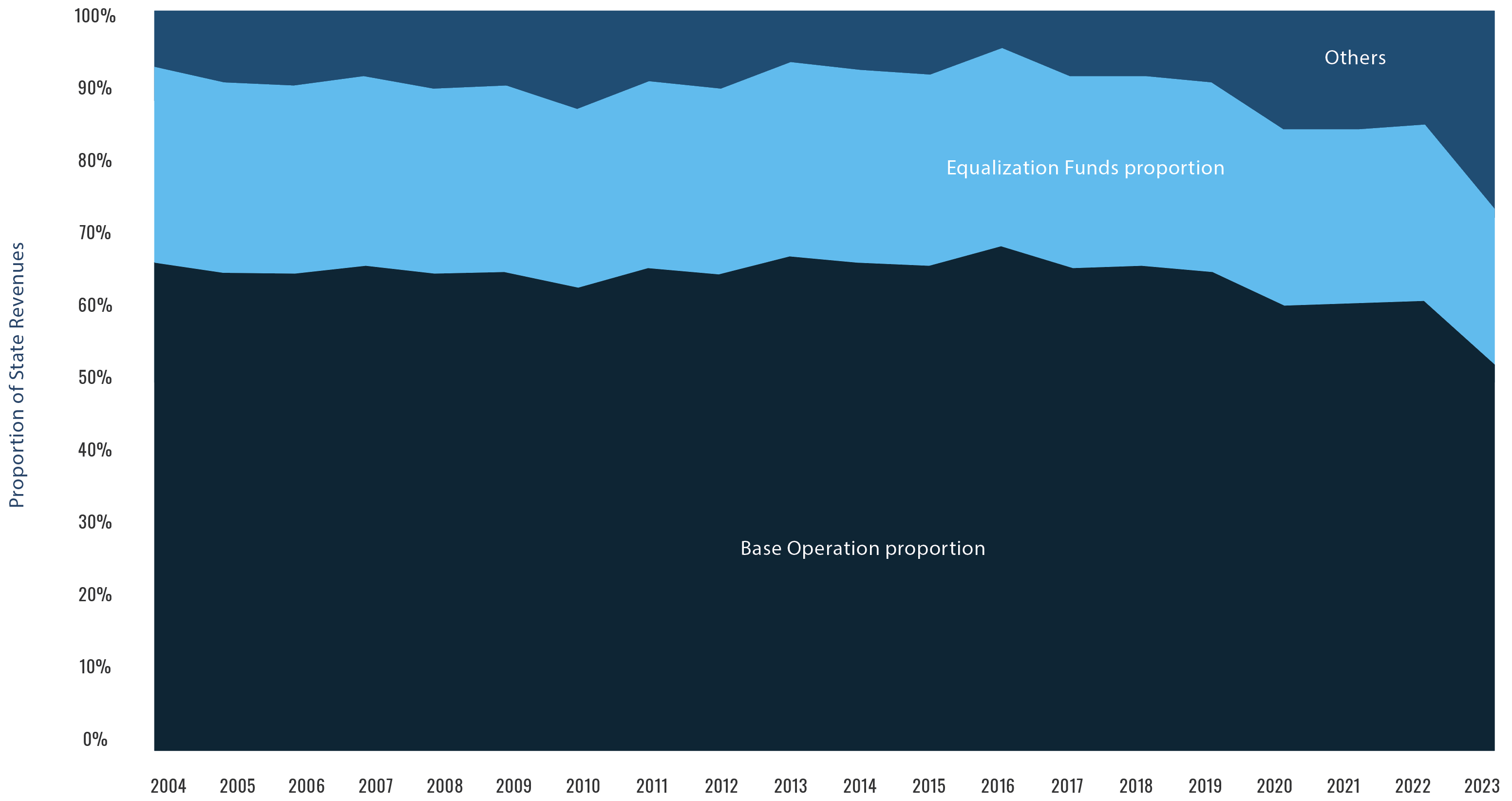

Each year, the Illinois Community College Board (ICCB) and Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE) make budget recommendations, which they submit to. However, approved budgets have decreased general fund appropriations to community colleges from $469 million in FY2004 to $361 million in FY2023, accounting for inflation in 2023 constant dollars (Figure 7). Each year, about two-thirds of state appropriations are distributed as base operating funding and one-fourth is allocated as equalization funds. The amounts of both sources have decreased over the years. The two categories make up nearly 90% of state appropriations from general funds distributed to Illinois community colleges (Figure 8).

Unrestricted base operating funds are allocated to individual colleges based on the number of credit hours they generate in six instructional categories (baccalaureate, business, technical, health, developmental education, and adult education). However, this total reimbursable cost is calculated after deducting tuition revenues and local tax revenues and, because legislators never fully fund ICCB recommendations, it is then prorated based on available state appropriations. The total annual deficit due to proration has increased from $98 million in FY2010 to $637 million in FY2021. Within the same period, the cost of delivering reimbursable credits generated by community colleges has almost tripled and the unfunded portion has increased from 33% in FY2010 to 78% in FY2021.34

Figure 7: Inflation-Adjusted State Appropriations from General Funds to Illinois Community Colleges

Note: Authors’ representation of data from the ICCB Data Book and IBHE annual reports.

Figure 8: Proportion of Funding Components of State Appropriations (FY2004-FY2023)

Note: Authors’ representation of data from the ICCB Data Book and IBHE annual reports.

Funding for Developmental Education

In 2021, Illinois adopted the Developmental Education Reform Act (DERA) as part of broader legislation (HB 2170) to address access inequities related to developmental education — it did not, however, change how developmental education is funded. When historically underrepresented students enroll at two-year colleges in Illinois, they are disproportionately placed in developmental education courses which can slow their ability to complete college-level courses, exhaust their financial aid, and lead to lower graduation rates (Table 1).35 This trend is consistent with national statistics, which suggest that the unintended negative outcomes related to developmental education exacerbate inequity in college access, affordability, and completion.36 Continuing a trend that began even before DERA was passed, the percentage of Illinois students enrolling in developmental education has decreased but the way colleges are reimbursed for credit hours creates perverse incentives to continue to place students in these courses.

On the surface, all credit hours are prorated at the same rate. For example, in FY2022, the weighted unit cost of delivering each credit hour in health was $684 and in developmental education it was $360.37 Community colleges receive $149 from tuition revenue and $193 from local tax revenue ($342 in total), leaving $342 in each health credit and $18 in developmental education credit uncovered. Applying state proration at 23%, community colleges receive $79 in each health credit delivered and $4 in each developmental education credit. In other words, for each health credit community colleges bear $264 uncovered cost but only bear $14 uncovered cost for each developmental education credit. On average, across the six instructional categories, $129-$159 is uncovered for each credit delivered, resulting in total revenue losses between $4 million and $112 million for individual community colleges in FY2022. Community colleges that offer a larger proportion of credits in high-cost health seem to bear a higher level of uncovered cost per credit hour, while colleges that offer a larger proportion of credits in low-cost developmental education seem to bear a lower level of uncovered cost per credit hour (Figure 9).

Table 1: Enrollment in Developmental Education and Graduation Rate by Student Groups at Illinois Community Colleges in 2019

Figure 9: Average Uncovered Costs per Credit Delivered based on Proportion of Credits (FY 2022)

Note: Authors’ representation of data from the Illinois Community College Board (2023).

Other State Appropriations

Despite the intentional design of the equalization grant program to reduce the disparity of local property tax funding across districts, equalization does not adequately address inequities across the state’s community colleges. According to the Civic Federation, the formula for calculating equalization grants overlooks the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law which structurally limits how much property taxes may increase in 39 Illinois counties and influences how much local revenue can be raised and distributed to community colleges.38 Thus, the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law may lead the equalization grant formula to overestimate how much local revenue some districts receive, thus reducing their equalization grant allocations (though one such district, City Colleges of Chicago, receives $15 million annually to attempt to correct for this). Like base operating funds, the total equalization appropriation is also prorated and underfunded by an average of $80 million each year. Even when there is a mechanism in place to equalize funding disparities, Illinois community colleges are still asked to do more with less.

States can distribute general fund windfalls as one-time monies or special grants and contracts without influencing recurring base funding. The remaining 10% of state appropriations to community colleges appear to include non-base appropriations in the form of small college grants, performance-based funding (PBF), and other statewide initiatives (see the “Others” category in Figure 8)39. Since FY2005, college districts with 2,500 or fewer full-time equivalent (FTE) students receive a small, flat college grant of $50,000 to offset budget burdens related to fixed operating costs that are similar to larger colleges, like maintaining a building, but that they have fewer tuition dollars to defray. After proration, this budget item represents about 0.2% of total state appropriations to community colleges. While PBF has been intensively discussed in state funding literature, it has never carried major policy influence in Illinois because of the small percentage of funding attached.40 Beginning FY2013, Illinois started to allocate less than 1% of state appropriations to Illinois community colleges based on a new set of PBF measures. However, the actual allocation represents about 0.1% of total state appropriations from general funds, translating into individual college revenue between $1,000 and $30,000.

Illinois Community College Affordability: Tuition and Fees as Revenues

Between 2004 and 2020, the inflation-adjusted average published in-district tuition and fees have increased from $2,610 to $4,310 in Illinois, consisting of a $1,430 increase in tuition and a $270 increase in fees (Figure 10). Although federal grants like Pell and the state-funded Monetary Award Program (MAP) grants can largely cover tuition and fees, they may not be sufficient to offset students’ additional expenses such as books, room and board, and commuting costs. On average, community college students living with their families incur additional expenses of around $4,000. Community college students living independently off campus need to budget an additional $7,000 on average for room and board each year.

Figure 10: Community College Expenses for Students Not Living with Family and Portion of College Costs Covered by Financial Aid (2004-2020)

Note: Authors’ calculation based on data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System and Illinois Student Assistance Commission.

While scholarships and grants from federal sources have increased over the years and many of them are applicable to costs beyond tuition and fees, average MAP grants received by each recipient have been around $1,000 since FY2004 — and they can only be applied to tuition and fees.41 In other words, although the MAP formula allowed awards to be larger, the average award given to students has stayed around $1,000, failing to keep pace with the increasing cost of attending an Illinois community college. Moreover, many students never received MAP grants at all because the program is underfunded with too many students applying for too few dollars.42

The annual uncovered cost (Figure 10) is around $3,500 for community college students living with family and $11,000 for students living independently. In 2023, Governor Pritzker and the Illinois Student Assistance Commission moved to increase maximum MAP awards and raised the average award for community college students to about $1,500.43 However, as long as community colleges have to increase tuition and fees to make up for inadequate state appropriations, MAP awards will have to perpetually increase to support affordability.44

There are five last-dollar promise programs funded by mixed sources like community colleges and private donors. These programs enable students in select school districts to attend local community colleges including Carl Sandburg College, City Colleges of Chicago, Illinois Central College, and Richland Community College.45 Recent studies on promise programs indicate that students benefit from learning about the “free” college opportunity and/or receiving promise scholarships as indicated by improved college attendance, persistence, and degree completion.46 After adopting promise programs, community colleges expanded their first-time, full-time enrollments by 9-22%, especially for Black and Latinx students.47 Because promise programs are funded with a mix of public and private sources and have different design features, their influence on student success can vary.48 For example, last-dollar promise programs are often criticized for subsidizing middle- or high-income students.49

It is critical to note that state-funded grants and scholarships directly subsidizing community college students can improve affordability, but these non-operating grants should not be considered an alternative to state appropriations directly allocated to community colleges. That is, while need-based financial aid positively relates to students’ college attendance, academic performance, persistence, and completion, it does not necessarily serve as a tuition control policy.50 In fact, published tuition and fees can increase upon additional financial aid being available to students.51 To reverse the trend of community colleges’ overreliance on tuition and fees as revenue, unrestricted state appropriations that can be used at community colleges’ discretion are irreplaceable.52 To enhance student success, community colleges need to increase investment in instructional activities and other wraparound services.53 Adequate state funding would allow community colleges to increase institutional expenditures while maintaining affordability with sufficient levels of financial aid to students.

Section IV

Alternative Approaches for Distributing State Funding and Adequately Supporting Community Colleges

Illinois has a robust community college sector, but it needs investment. The state has failed to fully fund ICCB’s calculations of institutional need for decades, with the unfunded share of the request increasing over time. Additionally, community college funding formulas have run on autopilot for years, with the assumption that mechanisms like the equalization and small college grant programs ameliorate the worst of the budget inadequacies. However, each allocation is diluted by proration. Whatever the formula dictates, disbursements are always capped by appropriated funds. With low allocations, budgets are always balanced on the backs of community colleges and their students.

Through recent efforts such as the Developmental Education Reform Act in 2021 and an unprecedented expansion of MAP in 2023, Illinois is making important strides toward rebuilding the historic strength of its higher education sector in the 21st century.54 Moving toward adequately funding community colleges should complement and bolster recent legislative victories. We briefly introduce four ways that advocates can push for adequate funding for Illinois community colleges.

1. Fully Fund ICCB Grants and Reduce Tuition Reliance

Between FY2004 and FY2023, inflation-adjusted allocations to community colleges decreased from $469 million to $361 million annually. Those funds were then prorated so that community colleges were unreimbursed for much of their operating costs. As mentioned above, the total annual deficit due to proration reached $637 million in FY2021. At the same time, the state has failed to fund most of the cost (78%) of delivering reimbursable credits, which results in a substantially underfunded mandate on Illinois community colleges.55 By 2023, the state only paid 23% of the cost of instruction. The underfunding leads community colleges to pass on the state’s unfunded share to students and families by raising tuition and fees. Additionally, underfunding the cost of delivering courses makes it difficult for community colleges to expand high-cost and high-need programs like nursing relative to low-cost courses like developmental education.

Legislators and advocates should push for adequately funding Illinois community colleges by fully supporting ICCB’s annual grant need calculations. The state’s historic disinvestment did not reduce the cost of educating Illinois students or incentivize greater effectiveness or efficiency — it merely shifted the burden of operating public community colleges to local property taxes, students, and parents (Figure 5). In other words, the state has depended on student tuition and property tax revenues to make up for its inadequate support.

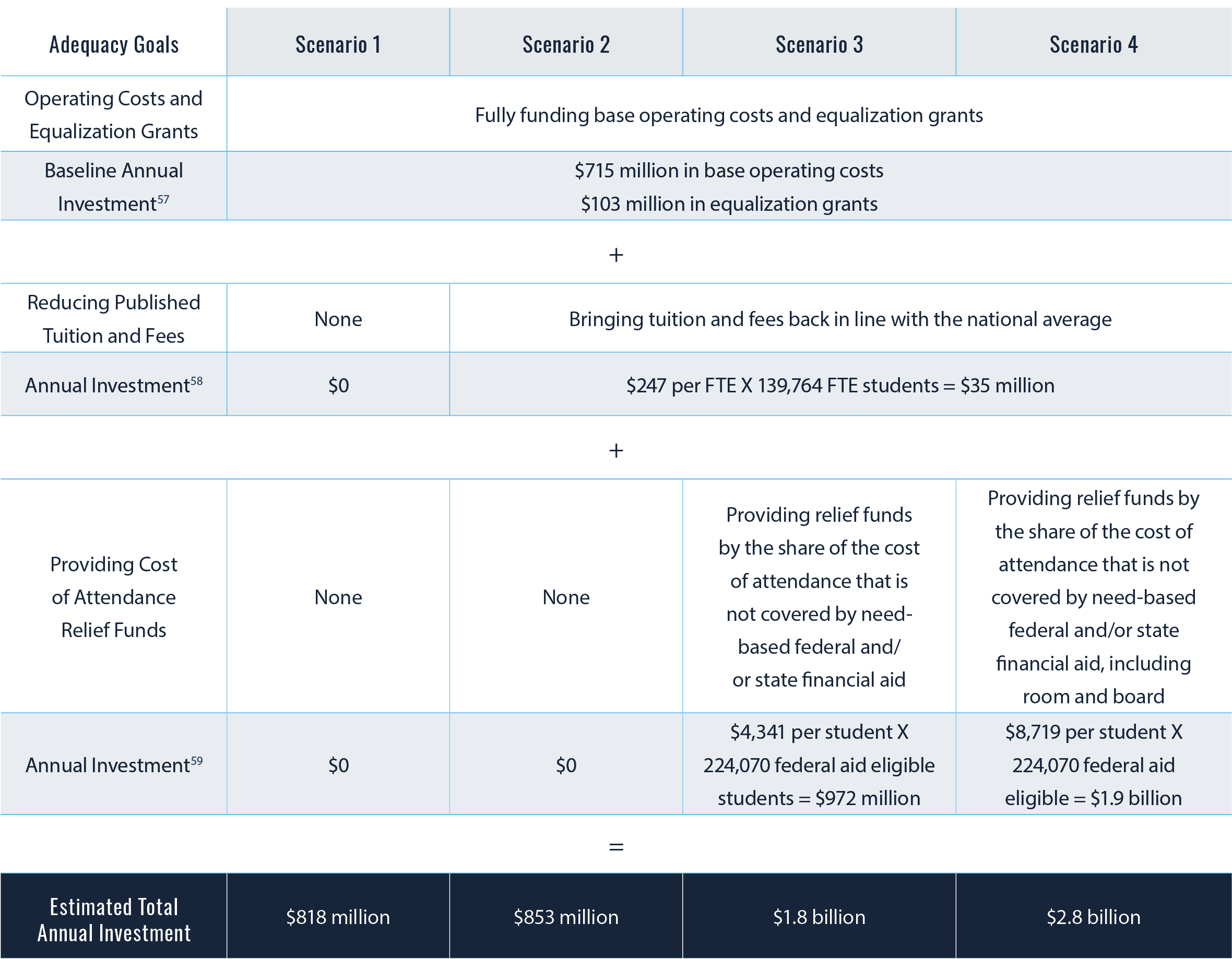

Scenario 1

Fully funding base operating costs and equalization grants.

Based on ICCB data, the state should have appropriated almost $637 million more in base operating grants and over $92 million more in equalization grants to community colleges in FY2021 (as presented in Scenario 1 in Table 2 below).56 Backfilling this underfunded mandate would satisfy current formula calculations and fund colleges for their share of the cost of meeting the state’s education and workforce preparation needs.

Additionally, as the state underfunded its community colleges by prorating appropriations using existing formulas, colleges offset declining state appropriations by increasing tuition and fee revenue. In addition to adequately funding colleges, new state appropriations should also support tuition and fee relief for Illinois students and families. Our analyses throughout this report support three scenarios for adequately funding Illinois community colleges.

Table 2: Estimated Adequacy Funding for Illinois Community Colleges and Illinois Students (in 2023 Dollars)

Scenario 2

Bringing tuition and fees back in line with the national average.

About ten years ago, Illinois closed the gap between the cost of attending a public community college in the state and the cost of attending a public community college around the country (as shown in Figure 3). Under this scenario, we propose the state require community college districts to reduce in-district tuition and fees to the national average and limit future increases to the cost of inflation. The state should then reimburse public community colleges for the tuition and fee revenue savings that were passed onto students.

Current Illinois community college students are responsible for the costs of tuition and fees, books and supplies, and other living expenses. Though the cost of attendance is offset for qualifying, low-income students by state financial aid and federal financial aid, there remains an unfunded gap for community colleges on average.

Scenario 3

Providing cost of attendance relief funds by the share of the cost of attendance that is not covered by need-based federal and/or state financial aid.

For many students who live with their families and do not have to independently pay costs of living, there is still an unfunded gap in the cost of attendance — in 2020 it was $3,668 (Figure 10). Under this scenario, we propose the state invest in tuition and fees relief funds for community college districts to either reduce published in-district tuition and fees or offer institutional aid for financially needy students to fully cover the cost of attendance.

Scenario 4

Providing cost of attendance relief funds by the share of the cost of attendance that is not covered by need-based federal and/or state financial aid, including room and board.

The unfunded cost of attending community college in Illinois is even larger for students who are older, working, or are parents who live independently from their families. For those students who do not have familial financial support, the cost of room and board and associated expenses averaged $7,367 in 2020 (Figure 10). Under this scenario, we propose that, in addition to subsidizing unmet needs associated with in-district tuition and fees, books and supplies, and other expenses such as transportation, the state should provide students with additional aid or a voucher for room and board. State aid to support the cost of living could be allocated similarly to the Post 9/11 GI Bill’s monthly housing allowance, encouraging students to attend college full-time instead of working and going part-time. 60

We estimate the total annual investment of adequately funding Illinois community colleges and serving students under various scenarios in Table 2. On the low end (Scenario 1), we estimate the state would be able to remove the underfunded mandate with $818 million. To bring published tuition and fees back in line with the national average, the state needs to provide another $35 million (Scenario 2). With additional investment of $972 million, the state could eliminate uncovered cost of attendance and make college more affordable for financially needy students (Scenario 3). Finally, the state could even support independent students who do not live with their families by offsetting the costs of room and board (Scenario 4).

Overall, eliminating the processes of prorating funds would reduce administrative burdens to ICCB and to community college districts. A recent IBHE report proposed using a set of adjustments to supplement base appropriations to the state’s four-year universities.61 We argue that for community colleges, the state should focus on fully funding ICCB recommendations for existing formulas, rather than creating new formulas which will not be effective either without significant additional funding. Further, fully funding existing formulas would avoid potential challenges with placing new, high-stakes reporting requirements or “compliance costs” on underfunded and understaffed community colleges.62 Many of the IBHE adjustments focus on providing additional support based on how well colleges enroll students from various groups (including those who are racial and ethnic minorities, from rural areas, or of non-traditional ages), which may make sense for highly selective research university contexts where those students are underrepresented. However, those ‘non-traditional’ students have historically been over-represented in community colleges. Rather than adjustments, community colleges need to be fully and adequately financed to serve the students they have always enrolled. Now is the time for state policymakers to improve processes for distributing funds as well as increase general fund appropriations to public community colleges.

2. Fund Implementation for Developmental Education Reform

In principle, state legislators recently recognized that it was time to reform developmental education. Community colleges have been tasked with spearheading design and implementation of transitional and corequisite courses as one strategy for reducing reliance on traditional developmental education. As the state navigates the process of offering guidance and financial support to implement the Developmental Education Reform Act, it should be aware of potential pitfalls. For example, when the Florida legislature failed to provide additional appropriations to help institutions implement developmental education reform, community colleges had to reallocate substantial resources ($31 million) from other areas to cover increased demand. This was not only to cover instructional costs but also to support wraparound services like tutoring, early alert systems, and advising that support student success.63

As previously mentioned, the state has an unfortunate precedent of covering a relatively small share of what it costs to offer courses. This may create a perverse incentive, leading campus administrators to think it is less of a financial loss to offer low-cost developmental education courses than higher cost courses in areas like health professions. Funding for developmental education reform should incentivize community colleges to adopt co-requisite models that make limited use of developmental education courses and instead prioritize placing students in college-level courses and helping them succeed. New funding could support co-requisite pathways with wraparound student services that provide holistic structure and guidance rather than entrenching separate developmental education and college-level tracks of courses.64

3. Invest Additional State Funding to Support Equitable Student Success

Focusing on neutrality or fairness to smooth out funding disparities across districts has not closed equity gaps or led the state to complete its goal that 60% of adults attain a postsecondary credential by 2025.65 Not only is overall achievement insufficient but, as shown in Figure 2, college attainment is actually getting worse for Black Illinois residents. Unlike other demographic groups, a smaller share of younger Black residents have college credentials compared to older ones. Additionally, to meet broader completion targets, the state needs to ensure that it is supporting groups that are growing more quickly and making up larger shares of the state population, such as Latinx students. Disparities in access, resources, and support have long driven attainment disparities for Black and Latinx students in Illinois and must be addressed to equitably meet state goals.

Adequately funding community colleges would allow them to increase expenditures in both curriculum and co-curricular programs to support student success without cutting funding from other areas. Research has repeatedly shown that solutions to increase student success require additional institutional expenditure.66 For example, in New York and Ohio, the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) has been successfully implemented to support community college success by expanding student services, course enrollment, and financial support.67 According to a 2015 report, “the direct cost of the ASAP program is $14,029 per program group member over three years. This estimate includes $6,238 on administration and staffing, $2,927 on student services, $1,558 on course enrollment, and $3,305 on financial supports.”68 In New York, it led to nearly doubling graduation rates.69 Although the price tag may seem hefty, the three-year investment per student is substantially less than what Illinois invests to support a full-time student at four-year institutions for a single year ($22,097) — more than twice the national average.70

4. Develop Accountability Paradigms that Encourage Innovation

Along with making the case for additional funding, advocates should lead policymakers in developing novel approaches to accountability that will encourage innovation, identify good practices, and lead to transformational change. New accountability metrics should avoid traditional cost-benefit analysis where outcomes are measured in dollars. Instead, community colleges should focus on increasing effectiveness, where analysts focus on “judging effectiveness by comparing the costs of alternative approaches that achieve the same outcome.”71 Traditional approaches, such as performance-based funding, reward (or punish) changes in outcomes without considering why or how the changes occurred. This has allowed colleges to change admissions policies and has led to concerns about using grade inflation to manipulate outcomes without changing how they support students. Focusing on effectiveness would mean preserving access and instead experimenting with changing staffing and service delivery with the ultimate goal of scaling promising and cost-saving practices. When accountability focuses on effectiveness, gains over time can be examined at the system, campus, or classroom level.

Additionally, practices should be assessed for whether they are effective in achieving similar outcomes across subgroups of students. For instance, encouraging students to enroll in online classes might be seen as a way to reduce costs and serve rural students but it can undermine broader accountability efforts when it has detrimental effects on degree completion among underrepresented students of color.72 Instead, funding policies should focus on expenditures based on educating the current student population for each community college. The associated costs of practices that equalize student success and completion rates, such as developing semester-by-semester education plans and providing academic and basic needs support to individual students, should be considered in defining funding adequacy.73

More specifically, advocates may consider asking for additional resources and capacity to widely adopt the use of cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost-effectiveness analysis is “an approach that identifies which strategies will maximize outcomes for any given cost or produce a given outcome for the lowest cost.”74 One relevant example comes from an experimental re-enrollment campaign that was carried out at multiple community colleges in Florida. The researchers calculated that “the combination of an informational nudge and one-course tuition waiver” ($303–$354) was a “relatively affordable” tool to incentivize students who have stopped out to return to community college.75 With an accountability approach that emphasizes effectiveness, states should give additional dollars to interventions that are found to be cost-effective and that improve equitable outcomes at system, campus, and classroom levels.

Section V

Conclusion

State policy discussions are shifting toward focusing on what it would mean to move toward an adequacy-based funding approach for public higher education.76 Illinois has a compelling opportunity to correct its historic disinvestment in its community colleges. In this report, we have identified some of the challenges caused by chronically underfunding community colleges including increased costs, declining enrollment, and unintended incentives for community colleges to track students into developmental education courses. Increasing state appropriations to adequately fund community colleges in Illinois could be paired with (a) fully funding ICCB base operating equalization grants and providing tuition and fee relief to Illinois students and families; (b) continuing the reform of developmental education; (c) improving student success and attainment; (d) adopting innovative approaches to accountability and effectiveness.

End Notes

- Table III-5, Illinois Community College Board 2023-2013 DataBooks. https://www2.iccb.org/data/data-characteristics/.

- 2.7% includes state higher education expenditures related to capital projects, community colleges, career and vocational education, professional schools like law, medical, veterinary, and nursing, student loan programs, and funding for private colleges and universities. NASBO (2023) 1991-2023 State Expenditure Report Data. https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/state-expenditure-report.

- Illinois Community College Board. (2023). Illinois Community College System. https://www.iccb.org/wp-content/pdfs/IL_Community_Colleges_System_Facts.pdf

- p. 29, Figure CP-20B, Ma, J., & Pender, M. (2023). Trends in college pricing and student aid 2023. College Board. https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Trends%20Report%202023%20Updated.pdf.

- Table III-5, Illinois Community College Board 2023-2013.

- p. 30, Figure CP-21, Ma & Pender (2023).

- Romano, R. M., & Palmer, J. C. (2016). Financing community colleges: Where we are, where we’re going. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Ibid. p.17

- Lumina Foundation. (2022). A Stronger Nation: Learning Beyond High School Builds American Talent. https://www.luminafoundation.org/stronger-nation/report/#/progress/state/IL.

- Manzo, F., & Bruno, R. (2017). High-impact higher education: Understanding the costs of the recent budget impasse in Illinois. Illinois Economic Policy Institute. https://illinoisepi.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/ilepi-pmcr-high-impact-higher-education.pdf

- United States Census Bureau. (2022). Current Population Survey, 2022 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. https://data.census.gov/

- p. 22, Illinois Board of Higher Education. (2021). A thriving Illinois: Higher education paths to equity, sustainability, and growth. https://ibhestrategicplan.ibhe.org/pdf/A_Thriving_Illinois_06-15-21.pdf

- Table CP-3 and Table CP-5, Ma & Pender (2023).

- Baker et al., 2022. Baker, B. D. (2018). Educational inequality and school finance: Why money matters for America’s students. Harvard Education Press.; Romano, R. M., & Palmer, J. C. (2023). Funding adequacy and the community college. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2023(203), 165-172.

- Baker, B. D., & Levin, J. (2019). Estimating the real cost of community college. In R. D. Kahlenberg (Ed.), Restoring the American dream: Providing community colleges with the resources they need. The Century Foundation.

- Kahlenberg, R. D., Shireman, R., Quick, K., & Habash, T. (2018). Policy strategies for pursuing adequate funding of community colleges. In R. D. Kahlenberg (Ed.), Restoring the American dream: Providing community colleges with the resources they need. The Century Foundation.; Desrochers, D. M., & Hurlburt, S. (2016). Trends in college spending: 2003-2013. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/Delta-Cost-Trends-in-College-Spending-January-2016.pdf

- Baum, S., & Kurose, C. (2013). Community colleges in context: Exploring financing of two- and four-year institutions. In J. Renker & J. Stafford (Eds.), Bridging the higher education divide: Strengthening community colleges and restoring the American Dream (pp. 73–108). The Century Foundation.; Dowd, A. C., & Shieh, L. T. (2014). The implications of state fiscal policies for community colleges. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2014(168), 53–63.; Jenkins, D., & Belfield, C. (2014). Can community colleges continue to do more with less? Change, 46(3), 6-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2014.905417.

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Total revenue of public degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by source of revenue and level of institution: Selected fiscal years, 2007-08 through 2020-21. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_333.10.asp.; Based on IPEDS definition: State appropriations are amounts received by the institution through acts of a state legislative body. Local appropriations, education district taxes, and similar support are amounts received from property or other taxes assessed directly by or for an institution below the state level. Federal non-operating grants are non-operating revenues from federal government agencies that are provided on a non-exchange basis (like Pell grants). State non-operating grants are non-operating revenues from state governmental agencies that are provided on a non-exchange basis (like MAP grants). Federal/state operating grants and contracts are revenues from federal/state government agencies that are for specific research projects or other types of programs and are classified as operating revenues.

- Trostel, P. A. (2012). The effect of public support on college attainment. Higher Education Studies, 2(4), 58–67.

- Dowd, A. C., Rosinger, K. O., & Fernandez Castro, M. (2020). Trends and perspectives on finance equity and the promise of community colleges. In L. Perna (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. 35), 517-588.; Melguizo, T., Witham, K., Fong, K., & Chi, E. (2017). Understanding the relationship between equity and efficiency: Towards a concept of funding adequacy for community colleges. Journal of Education Finance, 43(2), 195–216.; Mullin, C. M., Baime, D. S., & Honeyman, D. S. (2015). Community college finance: A guide for institutional leaders. Jossey-Bass.

- p. 31, Mullin et al. (2015).

- Illinois Board of Higher Education. (2021), p. 23.

- Kolbe, T., & Baker, B. (2019). Fiscal equity and America’s community colleges. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(1), 111-149.; p. 78, Figure 5.1, Baker et al. (2022)

- p. 79, Baker et al. 2022

- Kolbe & Baker (2019).; Tandberg, D. A. (2010). Politics, interest groups and state funding of public higher education. Research in Higher Education, 51, 416-450.

- D’Amico, M. M., Katsinas, S. G., & Friedel, J. N. (2012). The new norm: Community colleges to deal with recessionary fallout. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 36(8), 626-631. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2012.676506.; Mullin, C. M. (2010). Doing more with less: The inequitable funding of community colleges (Policy Brief 2010-03PBL). Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

- Bombardieri, M. (2020, October 28). Tapping local support to strengthen community colleges. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/tapping-local-support-strengthen-community-colleges/

- Dowd, A. C., & Grant, J. L. (2006). Equity and efficiency of community college appropriations: The role of local financing. The Review of Higher Education, 29(2), 167–194.

- Dowd, A. (2004). Community college revenue disparities: What accounts for an urban college deficit? Urban Review, 36(4), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-004-2083-z.

- Dowd & Grant (2006).

- Ibid. State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. State Higher Education Finance (SHEF) Report, 2022. https://shef.sheeo.org/state-profile/illinois/#how-does-funding-differ-by-sector.

- Dowd (2004); Dowd & Grant (2006)

- Bombardieri (2020)

- Illinois Community College Board. (2021). An overview of the Illinois community college system funding formulas. https://www2.iccb.org/iccb/wp-content/pdfs/agendas/2021/january/Item_6-2a_POWERPOINT.pdf.

- Illinois Board of Higher Education. (2021).

- Chen, X. & Simone, S. (2016). Remedial coursetaking at US public 2-and 4-Year institutions: Scope, experiences, and outcomes (NCES 2016-405). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.; Bahr, P. R. (2008). Does mathematics remediation work? A comparative analysis of academic attainment among community college students. Research in Higher Education, 49(5), 420-450.; Crisp, G., & Delgado, C. (2014). The impact of developmental education on community college persistence and vertical transfer. Community College Review, 42(2), 99-117.; Jaggars, S. S., & Stacey, G. W. (2014). What we know about developmental education outcomes: Research overview. Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University.; Jimenez, L., Sargrad, S., Morales, J., & Thompson, M. (2016). Remedial education: The cost of catching up. Center for American Progress.; Kurlaender, M., & Howell, J. S. (2012). Collegiate remediation: A review of the causes and consequences. Literature Brief. College Board.; Mazzariello, A., Ganga, E., & Edgecombe, N. (2018). Developmental education: An introduction for policymakers. Education Commission of the States.; Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2014). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(3), 371-393.; Scott-Clayton, J., & Rodriguez, O. (2015). Development, discouragement, or diversion? New evidence on the effects of college remediation policy. Education Finance and Policy, 10(1), 4-45.

- p. 4, ICCB. (2023). Fiscal year 2023 Operating budget appropriation and supporting technical data. https://www.iccb.org/wp-content/pdfs/fiscal_manuals/FY23TECHAPDX.pdf.

- The Civic Federation. (2018). An examination of the finances of Illinois community colleges. https://www.civicfed.org/civic-federation/blog/examination-finances-illinois-community-colleges

- The “Others” category includes small college grants, performance-based funding (PBF), and other statewide initiatives, excluding appropriations on the following items: high school equivalency testing, adult education programs, ICCB office operating budget, and Illinois Longitudinal Data System project. The proportion of the “Others” category has increased from 10% to 16% in FY2020, mainly driven by the $23.8 million Competitive Grant Program. The proportion increased again to 27% in FY2023 upon a series of initiatives with a total of $47.7 million, such as $25 million in Pipeline for the Advancement of the Healthcare (PATH) Workforce program, $5.9 million in Southwestern Illinois College Educational Facility, and $5 million in College Bridge Programs.

- Ortagus, J. C., Kelchen, R., Rosinger, K., & Voorhees, N. (2020). Performance-based funding in American higher education: A systematic synthesis of the intended and unintended consequences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 520–550. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720953128.

- Illinois Student Assistance Commission. (n.d.). Data book. https://www.isac.org/e-library/research-policy-analysis/data-book/.

- Illinois Board of Higher Education. (2021).

- Illinois Student Assistance Commission. Data book.

- Illinois Student Assistance Commission. (n.d.). Monetary Award Program (MAP). https://www.isac.org/isac-gift-assistance-programs/map/.

- Last-dollar awards are “reduced by financial aid received from the federal or state government and other sources” (Perna & Leigh, 2018, p. 156). In contrast, the amount of a first-dollar award is not influenced by whether students receive any other financial aid. Thus, last-dollar awards provide lower average awards to low-income students than first-dollar awards “as low-income students are typically eligible for federal and state need-based grant aid” (p. 156). Perna, L. W., & Leigh, E. W. (2018). Understanding the promise: A typology of state and local college promise programs. Educational Researcher, 47(3), 155-180.; The W.E. Upjohn Institute. (2023). Promise research at the Upjohn Institute. https://www.upjohn.org/promise/.

- Carruthers, C. K., & Fox, W. F. (2016). Aid for all: College coaching, financial aid, and post-secondary persistence in Tennessee. Economics of Education Review, 51, 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.06.001.; Meehan, K., Hagood, S., Callahan, K., & Kent, D.C. (2019). The case of Tennessee Promise: A uniquely comprehensive promise program. Research for Action.; Page, L. C., Iriti, J. E., Lowry, D. J., & Anthony, A. M. (2019). The promise of place-based investment in postsecondary access and success: Investigating the impact of the Pittsburgh Promise. Education Finance and Policy, 14(4), 572–600. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00257.; Pluhta, E. A., & Penny, G. R. (2013). The effect of a community college promise scholarship on access and success. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37(10), 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2011.592412.; Zumeta, W., & Huntington-Klein, N. (2020). State “free college” programs: Implications for states and independent higher education and alternative policy approaches. Council of Independent Colleges.

- Gándara, D., & Li, A. (2020). Promise for whom? “Free-college” programs and enrollments by race and gender classifications at public, 2-year colleges. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 603-627. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373720962472.; Li, A.Y., & Gándara, D. (2020). The “promise” of free tuition at public two-year colleges: Impacts on student enrollment. In L. Perna & E. Smith (Eds.), Improving research-based knowledge of college promise programs. American Educational Research Association.

- Billings, M. S., Gándara, D., & Li, A. Y. (2021). Tuition-free promise programs: Implications and lessons learned. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2021(196), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20485

- Though local promise programs that are last-dollar may encourage students to utilize all available federal and state-sponsored grant aid that they would not otherwise know about, lower-income community college students still rely on Pell Grants and state grants, and in reality, do not benefit much from promise programs with no financial need requirements. More detailed discussion by Billings et al. (2021) and Kramer, J. W. (2022). Expectations of a promise: The psychological contracts between students, the state, and key actors in a tuition-free college environment. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 44(4), 759-782. http://doi.org/10.3102/01623737221090265.

- Bettinger, E. (2015). Need-based aid and college persistence: The effects of the Ohio College Opportunity Grant. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1_suppl), 102S-119S. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373715576072.; Park, R. S. E., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2018). The impact of Pell Grant eligibility on community college students’ financial aid packages, labor supply, and academic outcomes. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(4), 557-585. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373718783868.; Kelchen, R. (2017). Tuition control policies: A challenging approach to college affordability. Midwestern Higher Education Compact.; Kim, M. M., & Ko, J. (2015). The impacts of state control policies on college tuition increase. Educational Policy, 29(5), 815-838. http://doi.org/10.1177/0895904813518100.; Weeden, D. (2015, September). Hot topics in higher education: Tuition policy. National Conference for States Legislatures.

- Bettinger, E. (2015). Need-based aid and college persistence: The effects of the Ohio College Opportunity Grant. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1_suppl), 102S-119S. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373715576072 Park, R. S. E., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2018). The impact of Pell Grant eligibility on community college students’ financial aid packages, labor supply, and academic outcomes. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(4), 557-585. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373718783868

- Kelchen, R. (2017). Tuition control policies: A challenging approach to college affordability. Midwestern Higher Education Compact. Kim, M. M., & Ko, J. (2015). The impacts of state control policies on college tuition increase. Educational Policy, 29(5), 815-838. http://doi.org/10.1177/0895904813518100 Weeden, D. (2015, September). Hot topics in higher education: Tuition policy. National Conference for States Legislatures.

- Robinson, J. A. (2017). The Bennett Hypothesis turns 30. James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.

- Barr, M. J., & McClellan, G. S. (2018). Budgets and financial management in higher education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Belfield, C., Crosta, P., & Jenkins, D. (2014). Can community colleges afford to improve completion? Measuring the cost and efficiency consequences of reform. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(3), 327-345. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713517293

- ICCB (2021).

- In 2023 dollars. Based on FY2021 data by ICCB (2021).

- In 2023 dollars. The estimated annual investment is the product term of the difference between published tuitions and fees in Illinois and the national average ($4,577 for Illinois and $4,330 for national average based on College Board data) and the number of FTE in Fall 2023 (based on ICCB enrollment report, https://www.iccb.org/wp-content/pdfs/reports/Fall_2023_Opening_Enrollment_Final.pdf).

- In 2023 dollars. The estimated annual investment is the product term of the unmet needs in 2020 for students living with their family and students not living with their family (as presented in Figure 12 and 13, respectively) and the total number federal aid eligible students in Illinois community colleges in 2020 (based on IPEDS data).

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2023). Post-9/11 GI Bill (Chapter 33) rates. https://www.va.gov/education/benefit-rates/post-9-11-gi-bill-rates/.

- Illinois Commission on Equitable Public University Funding. (2024). Report on the Commission’s Recommendations. https://www.ibhe.org/assets/files/Funding/Illinois_Commission_on_Equitable_Public_University_Funding_Report.pdf.

- Moynihan, D., Herd, P., & Harvey, H. (2015). Administrative burden: Learning, psychological, and compliance costs in citizen-state interactions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(1), 43-69.

- Mokher, C. G., Park-Gaghan, T. J., & Hu, S. (2021). Does the method of acceleration matter? Exploring the likelihood of college coursetaking success across four developmental education instructional strategies. Teachers College Record, 123(9), 3-27.

- Rosenbaum, J. E., Deil-Amen, R., & Person, A. E. (2007). After admission: From college access to college success. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Illinois Board of Higher Education. (2021).

- Belfield, C., Jenkins, P. D., & Lahr, H. E. (2016). Momentum: The academic and economic value of a 15-credit first-semester course load for college students in Tennessee. (CCRC Working Paper No. 88). Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University.; Gallard, A. J., Albritton, F., & Morgan, M. W. (2010). A comprehensive cost/benefit model: Developmental student success impact. Journal of Developmental Education, 34(1), 10-25.; Kolenovic, Z., Linderman, D., & Karp, M. M. (2013). Improving student outcomes via comprehensive supports: Three-year outcomes from CUNY’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP). Community College Review, 41(4), 271-291. http://doi.org/10.1177/0091552113503709.; Levin, H. M., & García, E. (2018). Accelerating community college graduation rates: A benefit–cost analysis. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(1), 1-27. http://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2017.1313087.

- Miller, C., & Weiss, M. J. (2022). Increasing community college graduation rates: A synthesis of findings on the ASAP model from six colleges across two states. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 44(2), 210-233. http://doi.org/10.3102/01623737211036726.; Weiss, M. J., Ratledge, A., Sommo, C., & Gupta, H. (2019). Supporting community college students from start to degree completion: Long-term evidence from a randomized trial of CUNY’s ASAP. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(3), 253-297. http://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170430.

- p. 71. Scrivener, S., Weiss, M. J., Ratledge, A., Rudd, T., Sommo, C., & Fresques, H. (2015). Doubling graduation rates: Three-year effects of CUNY’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) for developmental education students. New York: MDRC.

- Ibid.

- State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. (2022).

- pp. 4-5, Brint, S., & Clotfelter, C. T. (2016). US higher education effectiveness. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(1), 2-37.

- Ortagus, J. C. (2023). The relationship between varying levels of online enrollment and degree completion. Educational Researcher, 52(3), 170-173.

- Complete College America. (2023). Ending unfunded mandates in higher education: Using completion-goals funding to improve accountability and outcomes. https://completecollege.org/resource/EndingUnfundedMandates.

- p. 401, Levin, H. M., & Belfield, C. (2015). Guiding the development and use of cost-effectiveness analysis in education. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 8(3), 400-418.

- Ortagus, J. C., Tanner, M., & McFarlin, I. (2021). Can re-enrollment campaigns help dropouts return to college? Evidence from Florida community colleges. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 43(1), 154-171.

- Prescott, B., Koch, Z., & Jones, D. (2021). Considering a standard approach to determining institutional funding adequacy. The National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. https://sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/210407-Institutional-Adequacy-Paper-FINAL.pdf.; Cummings, K., Laderman, S., Lee, J., Tandberg, D., & Weeden, D. (2021). Investigating the impacts of state higher education appropriations and financial aid. State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. https://sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SHEEO_ImpactAppropationsFinancialAid.pdf.; Laderman, S., McNamara, Prescott, B., Torres Lugo, S., & Weeden, D. (2022). State approaches to base funding for public colleges and universities. SHEEO and NCHEMS. https://nchems.org/wp-content/uploads/SHEEO_NCHEMS_2022_StateApproaches_BaseFunding.pdf.